What Founders Miss About AI Adoption: It’s Not Features, It’s Transfer

Make it stand out

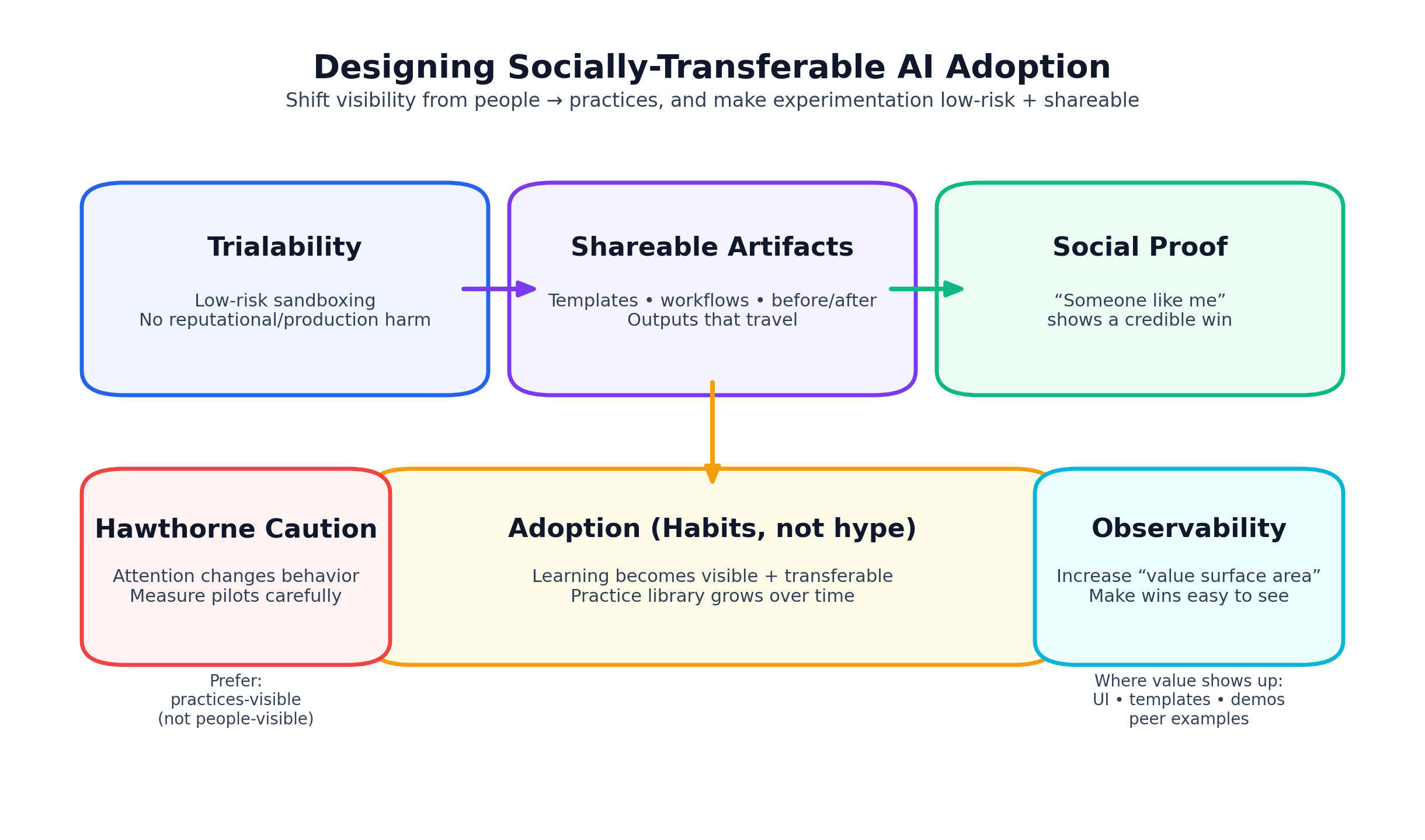

Founders often talk about adoption as if it’s an individual decision: a user tries the product, sees value, and then keeps using it. That story fits some products. But AI is a tool that reshapes work, and because of this, adoption tends to be a social process: people learn by watching, borrowing, and adapting what others do.

This is why “training” so often underperforms. Training assumes knowledge transfers as information. Yet the most important learning in complex tools is not informational; it’s situational: How do I use this in my workflow, with my constraints, and my risk tolerance?

Sahni and Chilton’s study of experienced Copilot users provides a vivid example of this mismatch (Sahni & Chilton, 2025). In their sample, formal training was never the primary way people learned. Instead, people leaned heavily on trial-and-error and peer exchange, even though most participants said formal training would be useful in principle (9/10) (Sahni & Chilton, 2025). That’s the surprising part: people can endorse training while still ignoring it.

For founders and CPOs, that tension points to an uncomfortable truth: users don’t just need instruction; they need permission and social proof. Permission to experiment without consequence. Proof that the tool fits their role and produces value. And the fastest way to provide proof is not an FAQ page—it’s a visible workflow artifact created by someone “like me.”

This is where diffusion theory becomes directly practical. Rogers describes observability as a key attribute affecting technology diffusion: if the results of an innovation are visible, diffusion is easier (Rogers, 2003). In product terms, observability is your “value surface area.” It’s how many places inside the product (and around it) show credible evidence of benefit.

The Hawthorne layer: visibility changes behavior (sometimes in the wrong direction)

The Hawthorne literature adds a second, humbling layer: attention changes behavior, but not always in predictable ways. The “Hawthorne effect” is when people change their behavior because they know they’re being observed. An example of this is when a team’s AI usage spikes during a highly visible pilot (dashboards, leader check-ins, weekly standups), but drops once the spotlight moves away—because the behavior was driven by attention, not integration into the workflow.

What it teaches us in accelerating tech adoption is (list at least 3 bullets):

· Measurement creates performance—so interpret “pilot lift” cautiously: attention can inflate short-term usage without durable habit change.

· Design visibility around outputs and practices (templates, before/after artifacts), not surveillance of individuals—otherwise you create anxiety, gaming, or avoidance.

· Use visibility as an adoption lever: spotlight repeatable workflows and peer examples to create social proof, not pressure.

· Expect distortion: if metrics become the goal, users optimize for the metric rather than the real value (quality, time saved, better decisions).

People learn how to use AI through experience, not through formal training, so the design choice to accelerate AI adoption is to shift visibility from people to practices. Make workflows, templates, and before/after outputs easy to share. Keep individual usage narratives less central.

Trialability is a product feature, not just a diffusion term

That’s also where “trialability” becomes a product feature, not a diffusion term. People want to try a product without creating reputational risk, breaking production, or otherwise negative effect. By offering trialability, founders/CPOs create habit change because users are given the chance to explore the product and apply it in a way that is personally relevant. Additionally, when experimentation is low-risk and shareable, the organization gets what it actually wants: a growing library of working practices.

Founder/CPO takeaways

· Treat learning as workflow discovery. Your product should help users find use cases, not just learn features.

· Design for observability. Make value visible through shareable artifacts, not more documentation.

· Use the “Hawthorne” approach carefully: visibility can distort. Aim for practices-visible / less individual narratives and solo stories.

· Build trialability into the product. Low-risk experimentation is the on-ramp to real adoption.

References

McCambridge, J., Witton, J., & Elbourne, D. R. (2014). Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(3), 267–277.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

Sahni, R., & Chilton, L. B. (2025). Beyond training: Social dynamics of AI adoption in industry